The beauty of progressive enhancement

posted on

Nokia released an updated version of its iconic Nokia 3310 about 3 years ago. It was affordable for me (€60/$65), so I had to get one. It came with a 2 MP camera, a battery that lasts 30 days (up to 22 hours talk time), 2G, 16 MB storage, the original Snake game, and a browser.

Screenshot: Nokia.

Opera Mini

You can access the worldwide web on the Nokia 3310 with Opera Mini. There are different versions of the Opera Mini browser, how it renders pages depends on the operating system, device, and settings you’re using.

If you install it on your smartphone, you probably won’t see any differences, because it uses the underlying browser engine on your Android or iOS phone. An interesting bit about this browser, though, is that you can set different data savings options (off, automatic, high, or extreme). When browsing in extreme mode requests are sent to one of Operas proxy servers which retrieves the web page, processes and compresses it, and sends it back. Opera claims that this reduces the amount of data transmitted up to 90%. This limits interactivity because JavaScript is processed only by the proxy server, and the device just renders it.

Some other notable things about JavaScript in Opera Mini:

- All scripts are allowed a maximum of two seconds to execute.

- setInterval and setTimeout functions are disabled.

- The number of events allowed to trigger scripts is limited.

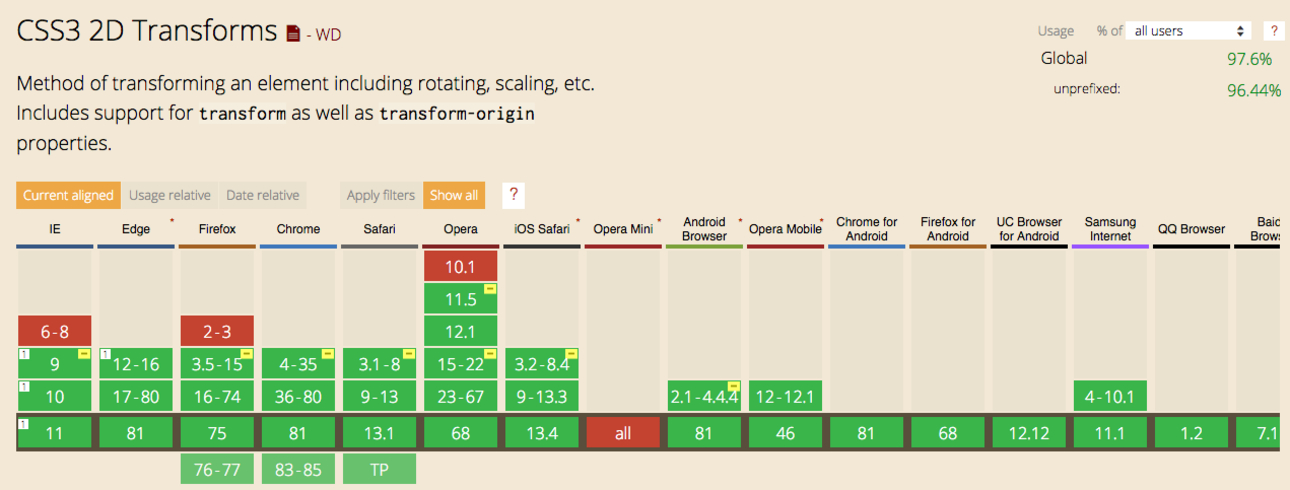

Opera Mini has a strong focus on performance and data saving. I guess that’s also one reason why it’s installed on my Nokia phone. Now, the browser installed on my 3310 is different to the Opera Mini version on my smartphone. It’s the one that’s usually presented in a beautiful red color on caniuse.com, if you search for almost any feature.

Progressive Enhancement

Yesterday I was curious and wanted to know if and how a website I recently made renders on the Nokia 3310.

Here’s a short demo of how the website looks like in Safari on an iPhone XR compared to Opera Mini.

To my surprise, I only had to reduce some paddings and font sizes to make it look nice.

I didn’t have to change much because I follow the Progressive Enhancement principle when I build websites. Progressive Enhancement focuses on content and enhances experiences layer by layer. Aaron Gustafson explains how we can apply Progressive Enhancement to web development in his iconic article “Understanding Progressive Enhancement“.

Image: A List Apart

Start with your content peanut, marked up in rich, semantic (X)HTML. Coat that content with a layer of rich, creamy CSS. Finally, add JavaScript as the hard candy shell to make a wonderfully tasty treat (and keep it from melting in your hands).

Aaron Gustafson.

How I’m applying Progressive Enhancement

I have some practical examples for you to help you better understand what Progressive Enhancement on the web means.

Grid

For the 2-column layout on the homepage of Front-end Bookmarks, I’m using CSS Grid. If a browser doesn’t understand display: grid it just falls back to a single column layout. Note that I don’t have to use feature queries because browsers just ignore properties they don’t understand.

ul {

display: grid;

grid-template-columns: repeat(auto-fit, minmax(29rem,1fr));

grid-gap: .7rem;

}

The single column layout isn’t ideal, but it's good enough.

Search

Modern browsers render a combo-box in the page's header that lets you browse, filter and select pages. In my JavaScript I want to use arrow functions, template literals, etc. without having to polyfill these features for less capable browsers. That’s why I’m sending JavaScript only to browsers that understand ES2015+. I do that by adding type="module" to my script tags.

<script src="/assets/js/scripts.min.js" type="module"></script>Browsers will only execute the script if they support JavaScript modules, and browsers that support modules also support ES2015+ features. Philip Walton introduced this technique in 2017 in his article Deploying ES2015+ Code in Production Today.

This rich JavaScript component falls back to a simple search form. The input field is pre-populated with the value “site:www.frontendbookmarks.com ”. If you add a search term to this string and hit the submit button, the search engine DuckDuckGo will open and search for the entered keyword on frontendbookmarks.com.

It’s not the best experience, but better than no experience.

<form action="https://duckduckgo.com/" method="GET">

<label for="search">Search on DuckDuckGo</label>

<input

id="search"

name="q"

value="site:www.frontendbookmarks.com "

type="text"

/>

<button type="submit">Search</button>

</form>I stole that idea from Zach who uses a similar solution for search in the eleventy docs.

I’m planning on improving the performance on Front-end Bookmarks by using the webp image format and lazy loading. I haven’t implemented it yet, but for both features I will also make use of Progressive Enhancement.

Webp Images

The advantage of webp is the file size, which usually is much smaller compared to other image formats. Unfortunately, I can’t just replace all my jpgs with webps, because Safari and IE don't support WebP, but we can give browsers options by using the picture element.

<picture>

<source srcset="image.webp" type="image/webp" />

<img src="image.jpg" alt="image description" />

</picture>Browsers read the picture element from top to bottom. If they support WebP, they will use the webp image defined in the source element. If not, they just skip it and use the jpg defined in the img tag instead.

Lazy loading

To optimize image loading performance, I’ll use lazy-loading which makes sure that images are only downloaded if they’re visible in (or close to) the viewport. I really don’t want to use a large third party script for that, instead I’ll go for native lazy loading with a fallback for browsers that don’t support it.

<img data-src="myimage.jpg" loading="lazy" />// Replace the src attribute with the value in the data-src attribute

// for browsers that support native lazy-loading.

if ('loading' in HTMLImageElement.prototype) {

const images = document.querySelectorAll("img[loading='lazy']");

images.forEach((img) => {

img.src = img.dataset.src;

});

} else {

// Fallback for other browsers

}Rahul Nanwani explains in his article The Complete Guide to Lazy Loading Images how a fallback for native lazy-loading might look like.

Update June 10, 2020.

This pattern uses Javascript to add the src attribute to the image. If JavaScript is not active in the browser, the image won’t show. We can work around that by progressively enhancing the pattern once more.

<img data-src="myimage.jpg" loading="lazy" />

<noscript>

<img src="myimage_lowres.jpg" />

</noscript>Content wrapped in noscript tags will only execute, if scripting is currently turned off in the browser. For that scenario, we can provide a low-resolution version of the image which is much smaller in file size.

Progressive Enhancement is beautiful

I’ve titled this post The beauty of progressive enhancement because it’s beautiful to see which shape an experience can take on different devices, operating systems, and browsers. Progressive Enhancement allows us to use the latest and greatest features HTML, CSS and JavaScript offer us, by providing a basic, but robust foundation for all.

Enabling people who use browsers like Internet Explorer 11 or Opera Mini to access content is essential. Don’t rely on browser statistics, think about who you’re building websites for. Our users are diverse, just like their physical abilities, personal preferences, and the devices and browsers they’re using.

Thanks for reading. ❤️

If you have more examples for progressive enhacement, please share them with me via e-mail.

Resources

- Opera Mini on wikipedia

- Using WebP Images by Jeremy Wagner

- Native image lazy-loading for the web! by Addy Osmani