The lang attribute: browsers telling lies, telling sweet little lies

posted on

The lang attribute is an essential component in the basic structure of an HTML document. It’s important that we define it correctly because it affects many aspects of user experience. Unfortunately, the negative effects a missing or wrong attribute can have aren’t always evident. Austrian news site orf.at learned that the hard way recently.

Applied to the <html> element, the lang attribute defines the natural language of a page. If your document is written in French, you would set it to fr.

<html lang="fr">

<head>

…

</head>

<body>

…

</body>

</html>Search engines, screen readers, browser extensions, and other software use this information.

Why is the lang attribute so important?

Adrian Roselli wrote about the Use of the Lang Attribute, so I will not repeat everything he says but I’ll give you some examples of how this attribute influences UX, and I will show you what happened recently on the most popular Austrian website in Austria.

Auto-translation

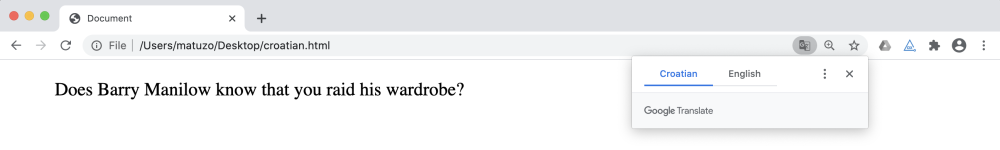

Translation tools like Google Translate may offer to translate contents of a page if the language defined in the <html> element is not the same as the default language in the browser. It seems it doesn’t matter in which language the page is actually written, what counts for Google Translate is the value of the lang attribute. In the following example, Chrome gives me the option to translate the Croatian text on the page, which isn’t Croatian, to English because I set lang to hr.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="hr">

<head>

…

</head>

<body>

<blockquote>Does Barry Manilow know that you raid his wardrobe?</blockquote>

</body>

</html>That makes sense and in principle it’s a useful feature but it can be problematic, if translations are not desired:

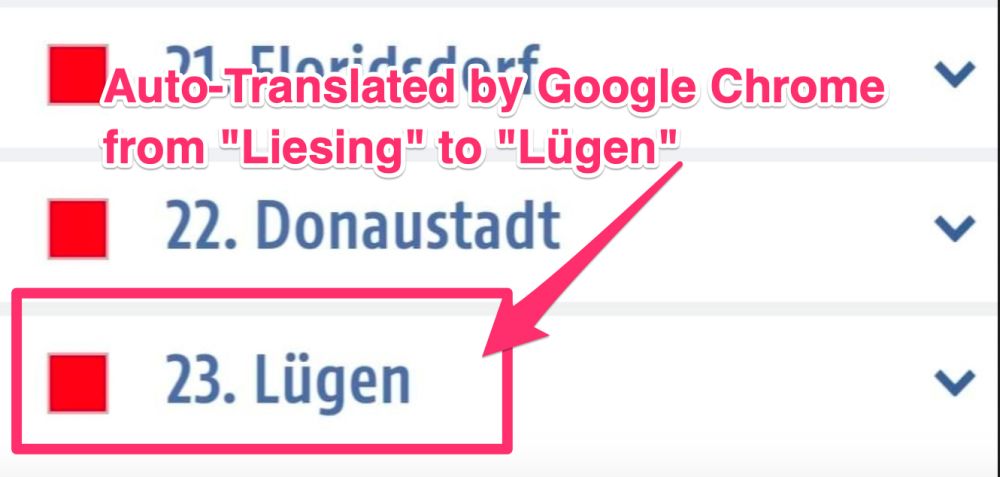

Vienna went to the polls this month to elect a (new) municipal government and orf.at published the results on their website. They split the results by district, from the 1st district “Innere Stadt” to the 23rd district “Liesing”. Soon after they’ve published the results, they received bug reports from users stating that some names of districts where wrong. When they tried to reproduce the bug, they noticed that Chrome offered to translate the page. If you just close the prompt, nothing happens, but if in the past you let Google Translate translate pages automatically, it wouldn’t ask anymore but automatically just translate the page.

The page was written in German but the natural language of the page was set to English in HTML (en), and that’s why Chrome users who instructed the browser to translate English to German automatically saw this:

Google Translate changed the name of the 23rd district “Liesing” to “Lügen” (to lie in English) and the name of the 10th district from “Simmering” to “Sieden” (to simmer in English). Google Translate assumed that the authors meant to write "lying" (lügen in German) and that "Simmering" isn’t just a name but the act of cooking liquids.

How did it happen?

First, I have that to say that it’s not a big deal. I’m just writing about it because it’s an interesting side effect of an issue that usually affects accessibility and not user experience in general.

I know some devs at orf.at and I also know that they care about quality and accessibility, so why did that still happen? Of course, because we’re all human and shit happens, but the specific problem on orf.at was that they’re using vue-cli, which automatically creates a boilerplate structure for documents that sets the lang attribute to en by default. The devs didn’t notice it because validators and automatic accessibility testing tools just check if the attribute is present and the value valid.

Preventing this bug

So, it’s a bug that’s hard to spot, but how can we prevent it?

- Frameworks and other setups that offer a boilerplate HTML structure could make picking the natural language part of the automatic or manual installation process instead of setting a default. The devs at orf.at already created an issue for vue-cli.

- The documentation should include a section about the HTML document structure and explain why certain things are important and which side effects a wrong implementation can have.

- You could use something like a11y.css to debug your document or create your own debug.css and add tests you want to run in your development environment. “Tests” sounds fancy, but it’s just a bunch of selectors that show a big red border or other visual indicators, if there’s an error.

Debugging the lang attribute

There are several things you can check.

- Is a

langattribute present? If not, show a red dotted border.

html:not([lang]) {

border: 10px dotted red;

}You could even display an error message.

html:not([lang])::before {

content: 'lang attribute missing';

display: inline-block;

background: red;

position: fixed;

top: 0;

left: 0;

padding: 0.3em;

color: #fff;

font-size: 1.2rem;

}Missing lang attribute demo on CodePen

- Is a lang attribute present but the value empty?

html[lang=''],

html[lang*=' '] {

border: 10px dotted red;

}Empty lang attribute demo on CodePen

- Does the lang attribute contain the correct value?

html:not(:lang(en)) {

border: 10px dotted red;

}Wrong value in lang attribute demo on CodePen

What’s great about using the lang() pseudo class is that this test will work even if the value is en-US or en-GB, etc.

Note: That won’t work on multilingual websites and you’ll have to adjust it for every project depending on the language.

- Putting it all together:

html:not([lang]),

html:not(:lang(en)),

html[lang=''],

html[lang*=' '] {

border: 10px dotted red;

}

html:not([lang])::before,

html[lang='']::before,

html[lang*=' ']::before,

html:not(:lang(en))::before {

display: inline-block;

background: red;

position: fixed;

top: 0;

left: 0;

padding: 0.3em;

color: #fff;

font-size: 1.2rem;

}

html:not(:lang(en))::before {

content: 'wrong value for lang attribute';

}

html[lang='']::before,

html[lang*=' ']::before {

content: 'lang attribute empty';

}

html:not([lang])::before {

content: 'lang attribute missing';

}Debugging the lang attribute on CodePen

As already mentioned, the lang attribute doesn’t just affect auto-translation but many other aspects of user experience. Here are two more examples:

Screen readers

Screen readers, the software people use to read content on a page, may pick a different voice profile according to the value of the lang attribute. If you set it to Russian (ru) but the language of the page is English, it may sound like someone’s talking English with a heavy Russian accent.

Steve Faulkner recorded a demo to show you the effects.

Quotation marks

Quotation marks may change depending on the the natural language of the page.

Quotation marks on an English page look like this:

Does Barry Manilow know that you raid his wardrobe?

<html lang="en">

<head>

…

</head>

<body>

<blockquote>Does Barry Manilow know that you raid his wardrobe?</blockquote>

</body>

</html>German:

Does Barry Manilow know that you raid his wardrobe?

<html lang="de">

<head>

…

</head>

<body>

<blockquote>Does Barry Manilow know that you raid his wardrobe?</blockquote>

</body>

</html>French:

Does Barry Manilow know that you raid his wardrobe?

<html lang="fr">

<head>

…

</head>

<body>

<blockquote>Does Barry Manilow know that you raid his wardrobe?</blockquote>

</body>

</html>You can learn more about quotation marks in CSS in Here’s what I didn’t know about “content”.

Others

The correct usage of the value also may affect hyphenation, WCAG compliance, input fields, spell checking and the default font selection for CJK languages (Chinese, Japanese, and Korean). Read Adrian Rosellis article (and the comments section) for details.