Why 543 KB keep me up at night

posted on

The question how good good enough is and at which point a website is ready to go online is keeping me busy lately. The web is in bad shape and it’s because we’re making it too easy on ourselves. “It’s online and works in most browsers” is not enough - we have to be much more considerate of what we’re putting online.

Some background: About three years ago I specialized in web accessibility. Now it’s not just my job to make sure that the websites I build are accessible, but the websites of others, too. I’m a front-end developer, but also a consultant and auditor. I’m employed for about a year now as well, and I have to evaluate a lot more third party web products than I used to.

Something has changed

A friend recently sent me the link to a website and asked me for feedback, because I had experience with the content management system their client was using.

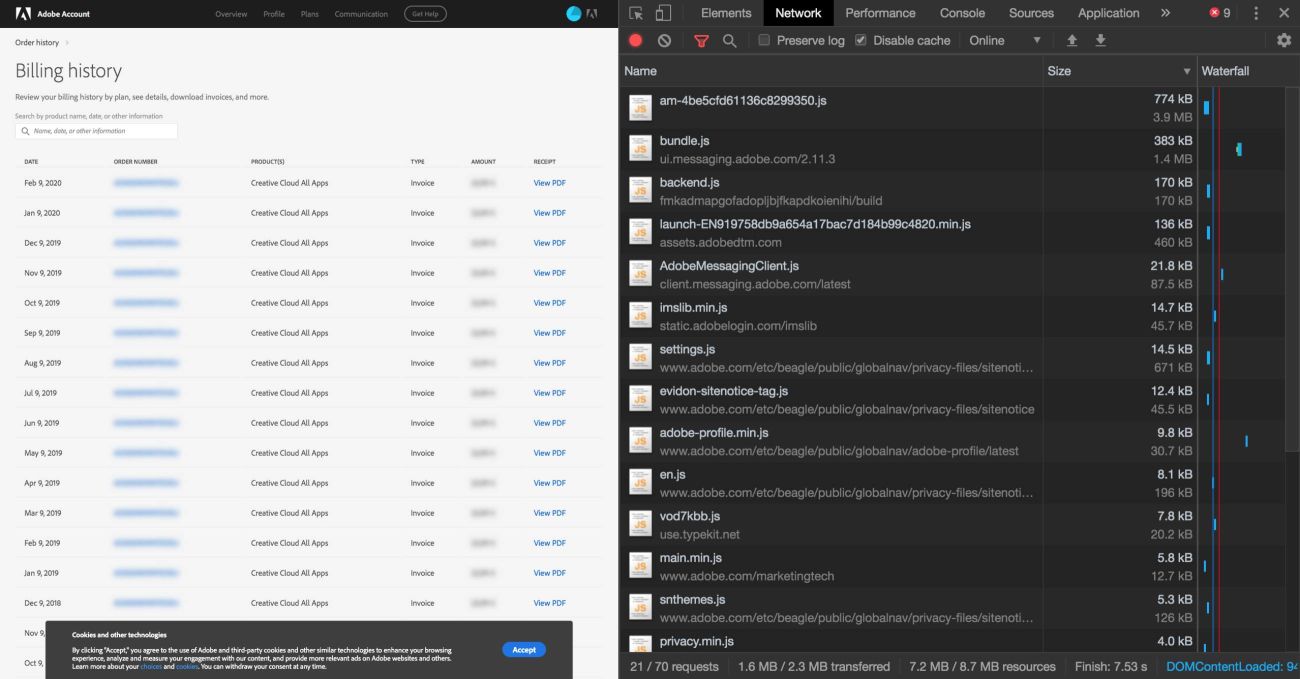

I checked a few things and then browsed through the website with Dev Tools and the network panel open. The homepage had a page weight of 4.1 MB (6.7 MB uncompressed). I thought, “Aight, that’s not great, but there are a bunch of images, so I guess it’s okay”. Then I visited a page with a header, footer, sidebar navigation and a short paragraph (543 KB / 1.6 MB uncompressed) and I thought “Nice, noticeably below 1 MB, that’s pretty good.”.

And then it hit me.

What the hell did just happen? 543 KB on a simple text-only page is OK? Fuck no, it’s not.

How and when did I get to the point where I would consider a page weight of 4 MB on a large page and 500 KB on a small page normal? This got me thinking (and writing obviously). This is not an exception. The quality of most websites I audit and evaluate is bad. Somehow we've collectively decided that it’s okay to publish garbage.

When I say we, I don’t just mean us developers. The reason could be a developer who doesn’t care enough, but it could also be a team lead, product owner or client who simply doesn’t give devs enough time to care about quality. Causes for that could be a lack of awareness, tough deadlines, short release cycles, or focus on development of new features instead of improvement of existing code.

When I say garbage, I mean slow, inaccessible, annoying, stressful, or intrusive web experiences.

Slow

I need 1.6 MB of JavaScript (7.2 MB uncompressed) to display a table with my billing history.

Inaccessible

Many accessibility issues derive from bad markup. I could show a screenshot of any website here, but you’ll find some common mistakes on HTMHell.

Annoying

No, the first thing I want to do when I visit your website is not to sign up for a newsletter.

Stressful

Only 5 rooms left! Limited-time deal!! 2 other people looked for your dates in the last 10 minutes!!! I will never ever book anything on your website!!!!

Intrusive

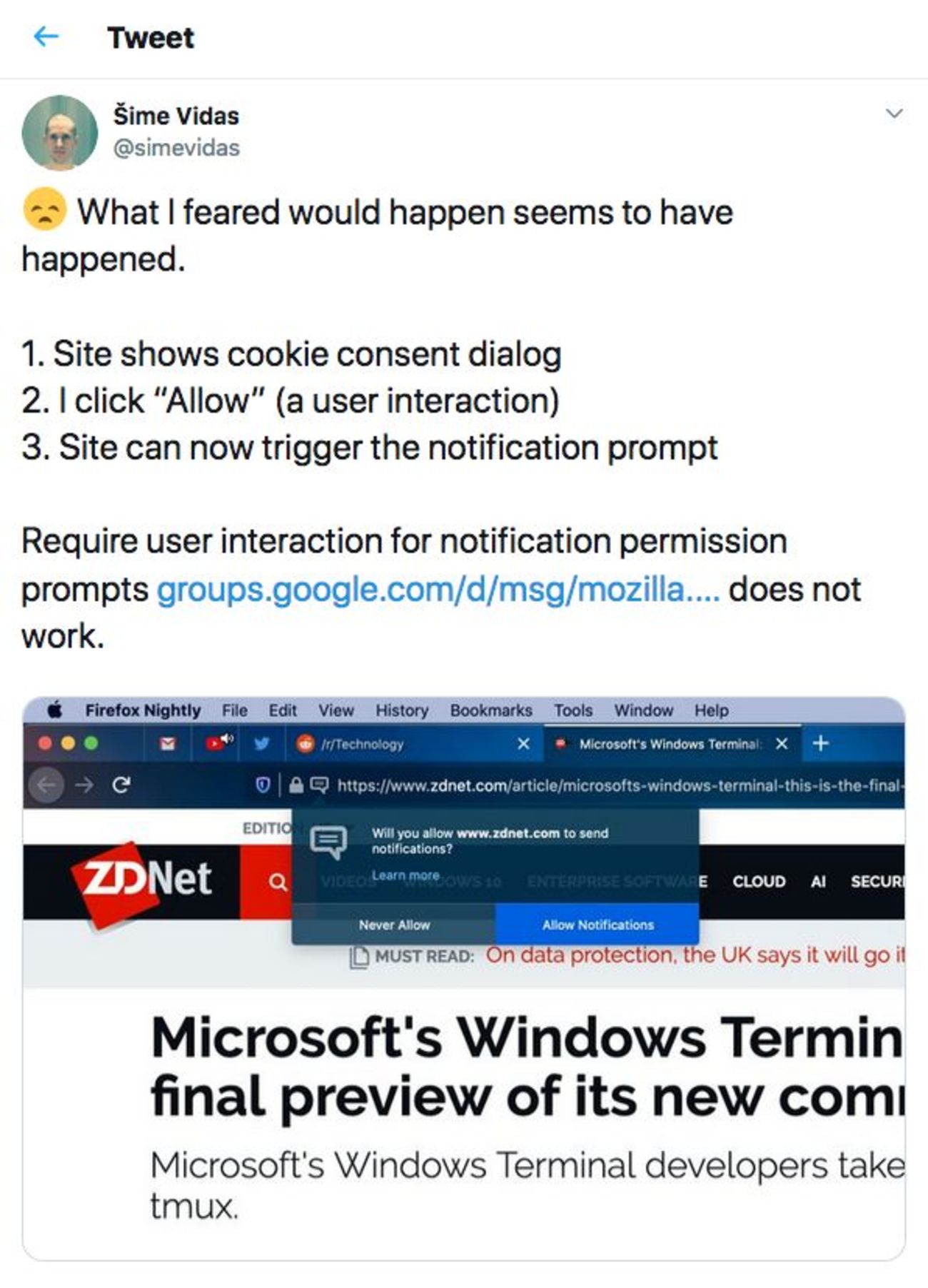

ZDNet misuses the cookie consent dialog to trigger the push notifications prompt.

I don’t know if it has always been like that or if the quality of what we publish online has gotten worse with advancing technological possibilities on the web (faster networks, more powerful tools and new APIs). The web is in bad shape - we need to readjust our understanding of what quality means and what we can expect our users to put up with.

Now you might think, “Dude, chill. 543 KB? That’s not bad, even on a 3G connection that site should load in a reasonable time.”.

Why 543 KB might be bad

Yes, I know, it depends. 543 KB aren't always bad, but on that specific page there’s only a single image (the logo ~20 KB) and a single paragraph. So why then is the page still relatively large, where are the remaining 523 KB coming from?

Let’s break it up and see what we could take into account when we evaluate the total transferred bytes.

Page weight

Even in times of 4G or 5G, optimizing for fast download is important. People don’t always surf the web under the best conditions. Build your website for someone who visits it at Starbucks using Starbucks WIFI and not for someone who’s connected to their own fast internet at home.

The website we’re talking about now is an Austrian website, in German language, accessed mostly by Austrians via Austrian networks. We’re a country with affordable and fast data. Don’t get me wrong, the page weight is definitely too big, but I’d argue that it's not the biggest issue, especially if they’re caching efficiently and prioritizing asset loading correctly (spoiler alert: they’re not… ).

DOM size

Many and deeply nested elements result in a large DOM tree, which can affect runtime, memory and load performance negatively.

A large DOM tree in combination with complicated styles might have a bad effect on page rendering. In his talk “The Intersection of Performance and Accessibility” Eric W. Bailey gives an example of a form based on Material Design that caused the screen reader Voice Over to crash because of its massive DOM size.

To make a material design radio input, you need six HTML elements containing nine attributes with a DOM depth of three. You also need 66 CSS selectors containing 141 properties which weighs in at 10k when minified. You also need 2374 lines of JavaScript which weighs in at 30k when minified. All of this will get you a radio input.

Another factor is JavaScript. Updating complex DOM structures can get expensive, changes at one level in the DOM tree can cause changes at every level of the tree, which leads to more time being spent performing reflow. DOM operations can become a performance bottleneck, but there’s more to consider, like storing references to a large number of nodes, which might overwhelm the memory capabilities of devices. Creating DOM nodes only when needed and destroying them when no longer needed helps with that.

If you don’t write your markup carefully and enable compression on the server, your HTML document might end up having multiple hundred kilobytes, although it should be somewhere in the lower tens.

By writing carefully I mean only creating DOM nodes you need and adding extra divs and spans only when necessary. In React, Fragments might help with that.

class Columns extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<React.Fragment>

<td>Hello</td>

<td>World</td>

</React.Fragment>

);

}

}A fragment just returns the content within the fragment without an extra wrapper div.

Google recommends less than 1500 nodes total, a maximum depth of 32 nodes, and no parent node with more than 60 child nodes.

CSS

There are 11 style sheets with a total weight of 97 KB (566 KB uncompressed). Only by looking at the numbers it’s hard to tell if there are a lot of unused rules in there, but 566 KB of minified CSS is definitely not something that can be ignored. I'm not saying that refactoring their CSS is a must, but I’d at least consider taking another look at what goes into the CSS bundle. Sometimes it’s not even our fault that bundle sizes are too big. Many content management systems or plug-ins come with huge JS and CSS files where only a fraction of the code is needed.

Another thing worth considering is splitting up the main CSS file by media feature, especially if the assets are served via HTTP2.

<!-- Downloaded and render blocking -->

<link rel="stylesheet" href="main.css" />

<!-- Downloaded but not render blocking if media query doesn’t match -->

<link rel="stylesheet" href="medium.css" media="(min-width: 768px)" />

<link rel="stylesheet" href="large.css" media="(min-width: 1024px)" />

<link rel="stylesheet" href="print.css" media="print" />Before HTTP2 this was kinda considered a bad practice, but with HTTP2 multiplexing, the number of requests that can be sent to the server at the same time is no longer limited. The big advantage of splitting CSS into multiple files is that browsers will download all of them, but only those needed to fulfill the current context will block rendering,

Read more about the topic in Harry Roberts fantastic article CSS and Network Performance.

Fonts

Font files can get pretty big, a good font loading strategy is essential. Fonts are sometimes a necessary evil, but one file is a 34 KB Font Awesome file. SVGs might be a better choice, because they're more flexible than icon fonts for animation and styling, and a SVG sprite with just the icons needed and not the whole set of icons might end up being much smaller.

It’s been years since I’ve used services like Font Awesome, SVGs have so much more advantages over icons fonts.

JavaScript and bundle sizes

There are 22 JS files with a total file size of 320 KB (886 KB uncompressed). This is way too much considering that there’s only a navigation and a share button on this page.

I will not bash JavaScript, I love JS and I enjoy writing it. I’m not great at it though, and I’d argue that most of us aren’t. Lack of knowledge paired with a language that can easily fuck up performance is dangerous. That’s why I’m very cautious of what I’m doing and which 3rd party plugins I’m using.

I’ve watched Addy Osmani’s The Cost of JavaScript the other day, which is also one reason I’m writing this article. I was blown away by so many things he said. Here’s a summary of my highlights:

- JavaScript is one of the most expensive parts of your site, reduce how much JS you ship.

- Small JavaScript bundles improve download speeds, lower memory usage, and reduce CPU costs.

- Avoid large bundles (50KB+).

- Post-Download, executing JavaScript is the dominant cost.

- The differences between a low-end phone and high-end phone are huge.

- Fast JavaScript means fast at download, parse and compile, and execute.

- Avoid large inline scripts.

- If possible, split your JS code.

- Audit JS regularly.

- Make performance part of the conversation.

- Stop taking fast networks, fast CPU, and high RAM for granted.

- Test on real phones and networks.

Watch the talk or read the article, I promise you’ll love it.

If you know more about performance than I do (and you probably do), you might be shouting at the screen “You didn’t consider this and that”. Fair enough, but this post is not about how to optimize those 543 KB. It was my attempt to show you that we can’t expect whatever we produce and put online to be fine. We have to be much more considerate, we have to take a second and third look, and constantly challenge our decisions. Sometimes, even just slowing down can make a difference. As Andy Bell recently discovered while reviewing a larger codebase, stepping back and ignoring time pressure for a moment can help with seeing things clearly.

We had two or three grid systems, some fluid type and some utility driven type that conflicted and a card component that was pretty much a website in itself. If I had slowed down and stepped back, I could have seen these problems, but I didn’t. So seriously, slow down and you will save so much time.

By the way, the 543 KB page scored 11 points on the Lighthouse performance test.

Why bother?

Why is a website I'll probably never visit again bothering me so much?

Because someone decided that it was good enough to go live. The problem is not this specific website or how fast it loads, but that shipping seems to be so much more important than performance, usability, accessibility, or user experience. Again, I know it’s not always up to us, because often we just have to publish something we don’t agree with, but the least we can do is to educate others why some decisions might be harmful, and try to improve things in whatever ways we can.

It’s becoming increasingly clear that web performance isn’t solely an engineering problem, but a problem of people.

Whats good enough?

I started this article with the question “how good is good enough”. I can’t answer it for all of us, because it depends on our personal experience and capabilities. What I consider good enough might not live up to the expectations of others, but there are standards and best practices we can follow.

Here are a few things I (as a front-end dev) believe have to happen before a website can go online.

- Validate your HTML.

- Test in many browsers. There’s a world beyond Firefox and Chrome. Check Opera, Firefox Mobile, Brave, Edge, or Samsung Internet, just to name a few. Safari can be a bitch, too.

- Test on low budget phones, if you really want to see how well your website performs.

- Run Lighthouse and try to score 100 in the accessibility, best practices, and SEO audits. Scoring 100 in performance is hard, but strive for a score above 90.

- Check how your site performs on a slow connection by throttling it in Dev Tools.

- Put your mouse aside and use your website with the keyboard only.

- Test your site with screen readers.

- Go through David Dias' fantastic Frontend Checklist.

There’s more, but if we all did at least that, our users would be much happier. I know you might be thinking: “We don’t have the budget for that.”. But that’s the point: you should have it. “It’s online and works in most browsers” is not enough. We have to make performance, accessibility, usability, and user experience part of the conversation.

By the time you’ve reached this paragraph, you’ve downloaded 837 KB of data. Can that be improved? Most definitely. Is this website 100% accessible? Probably not. Did you get the best possible user experience? I guess no, I don’t know shit about UX.

If my own website isn’t perfect, who am I to lecture you? Well it’s not about publishing perfect websites. That’s not possible for many different reasons, but it’s important that we’re conscious of what we’re shipping to our users. It’s important that we care about our users and about the quality of our products and that our standards become higher than they are at the moment.

Good websites need time.

Great websites need a lot of time.For content, for graphics, for interaction, for organization, for findability, usability, accessibility and that dash of delight that makes it special.

Don’t build throw-away websites, build websites that last.

Resources

- Performance and the Accessibility Tree

- Uses An Excessive DOM Size

- DOM performance case study

- Rendering Performance

- Innovation Can’t Keep the Web Fast

- 5G Will Definitely Make the Web Slower, Maybe

- Keeping it simple with CSS that scales

Big thanks to Max and Sven for helping me with this article. ❤️